h

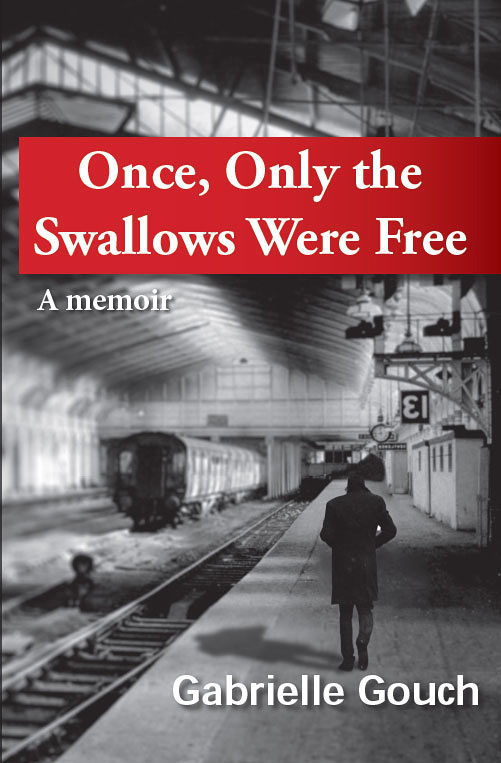

Once, Only the Swallows Were Free

Gabrielle Gouch

Hybrid Publishers 2013

The sweeping events of twentieth century Europe confront family love, chance and fate in this beautifully written treatment of ordinary lives in extraordinary times. Gabrielle Gouch's book is a deeply personal account of the journey her family must take to survive with the dream one day they will thrive, in Romania, Israel and Australia. Her sympathetic treatment of life with its impossible challenges, its deep disappointments, but its satisfaction in loves shared and opportunities grabbed...so that purposeful and in the end heroic people are made, resonates across cultures and borders...Gabrielle is passionate, caring and aware that the peace and comforts we share are lights amongst the darkness...

Richard Matheson, Goodreads

|

|

|

Read more, Once, Only the Swallows Were Free

‘Sweeping the front of the school was my duty. And there was a chief, of course. The chief street sweeper was an ex-office worker, some said engineer, sacked for being drunk on the job. His main duty was to prove that he was above us in every way. He walked around, erect in his fake leather jacket like a party chief. He was taller than himself. He inspected, he instructed, he was of a different opinion. Was the street swept? Was the rubbish removed? Where was the rubbish disposed of? “No, that’s no good, you need to sweep this again. You should not put the rubbish in that bin; the rubbish from the front of the building goes in the bin behind the building.”

One day he saw me sweeping and said, “You should do it from right to left.” “Right to left? Comrade, I can only do it from left to right, because of my hand.” I liked disobeying him, and watched for his reaction. “Of course you can. Just turn around!” he shouted. Did I care, left to right or right to left? I turned around and did it his way. He stood there and watched me, cigarette in his mouth. He was the chief.

The truth is that nobody wanted to do any work. Early in the morning, as I was finishing my night shift, the street sweepers would get together in my office. You see, I was the nightwatchman, but since I had to sweep the street in front of the building I was part of the group. They had to negotiate rosters and I had a warm office. They discussed who was going to swap with whom and who owed work to whom. At times such a hullaballoo would break out that if you hadn’t seen them you would have thought they were at each other’s throats. Half an hour later, with nothing sorted, they would decide to have a cup of coffee first, instant of course, then resolve who would do which section. There was no hurry; the chief would still be in bed at that time, probably with a hangover from the day before.’

‘Yoseftal, with its gathering of mismatched migrants, had a temporary feel about it. Was it the flimsy blocks of flats set out in a quadrangle in the middle of wasteland? Was it the lack of trees and vegetation? Or was it the nearly incompatible ways of life we brought with us that did not allow us to connect, to sprout roots? Apart from Romanians, there were migrants from Europe and Africa, India and Russia, Yemen and Morocco, educated and illiterate, religious and secular. We were the Yoseftali Tower of Babel.

We brought with us centuries of manners and habits which many could not or would not abandon. While the locals wore shorts and sandals with no socks, our middle-aged Romanian neighbour, on the lookout for a wife, never abandoned his suit and tie. And never found a wife.

In time, people who could afford better housing moved away. New migrants moved in. Some mean, some generous. Some believed in looking after the common property, but most did not. As time passed and the migrants churned through, almost no one cared. The block belonged to the state, so why should they pay for maintenance? Why should they pay for an electric bulb on the stairway? So they kept blundering up the stairs in the dark. And the council saw no need to impose regulations.

We shared our block entrance, the stray cats, the filth, the smells of cooking, appetising or nauseating, and willingly or unwillingly listened to each other’s music because the walls were thin and the music always loud. My father, who could not stand noise and could stand Oriental music even less, suffered in silence. Despite all that, I liked Yoseftal. During the short university holidays when I did not work, I would still be in bed when the old man with the donkey passed under our window calling out in Yiddish: “Old clothes, second-hand clothes!” It was a timeless and tired call, a sort of Middle Eastern ghetto call, as if all those centuries of otherness had migrated with us and taken root in the Promised Land. As if otherness was our destiny, and we would never escape it.

Later, I sat on the balcony having my breakfast and watching the old men returning from the synagogue. Among them was a religious Yemenite who lived next door, a tall thin man with a long white beard wearing an ankle-length white robe and clogs. A sort of Yoseftali Messiah. As he walked past, the bottle of arak poking out from under his robe bounced against his thin, bony body. He had been to the synagogue, but took a little detour on the way home. Soon sad Oriental songs mingled with slurred Arabic words came through the thin wall. Sometimes he would fall silent then suddenly loud, monotonous snores punctuated our conversation. At times he would wake up, tell his wife off, then get angrier and angrier, shout and thump while she sobbed and cried.

The other neighbours were different. The Azulais, a Moroccan family with twelve children, occupied two adjacent flats below us. Monsieur Azulai was blind but was off to work every morning. Madame Azulai could see everything except the filth. Nor could she smell the stench in their flat. She sat motionless on the sofa all day, but she had a heart of gold. For years after my father passed away, she often invited my mother. By then I lived in Australia and every time I returned for a visit, I would bump into her on the stairway and she would tell me off for leaving my parents. Her words hurt, deeply, but I knew she meant well. She felt sorry for my mother.’

Back to top

|