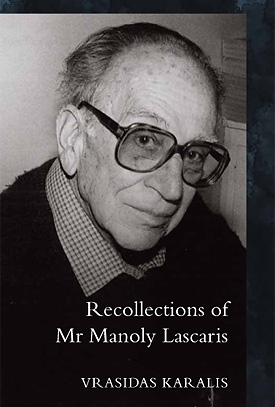

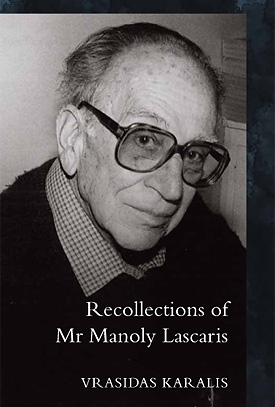

Vrasidas Karalis

Brandl & Schlesinger, 2008

I'd like to thank Diana Giese, my editor, for her inventive and imaginative interventions in the text Vrasidas Karalis

|

|

|

|

Recollections of Mr Manoly Lascaris, extracts

‘We were strolling through Centennial Park. It was early evening on an Arctic September day. Suddenly the wind started blowing with great force: dust and leaves in the air, dark clouds appearing from nowhere. The first drops of a Sydney storm sprinkled our skin.

"Let’s run back home through the crossing," he said. "It’s faster."

Around the Park is an old iron fence protecting the green haven from intruding cars. In order to get into the Park, you have to go around it. That takes ten minutes. But thirty metres on from where we stood, two iron rails are missing, and through this gap, Mr Lascaris, his dog and his friends would squeeze each time they went for a walk,

The storm made us run as fast as we could. When we arrived at the gap, Milly jumped first and crossed over the Martin Road footpath. The rain started pouring down. Mr Lascaris usually let me go first, following with a sardonic paternal smile. But on that occasion, without thinking, we both hurled ourselves simultaneously through the gap. We stuck, joined back to back, both trying to push through. He stopped out of astonishment; I stopped out of confusion. Neither knew who would make the first move.

Milly started barking at me. She ran up and bit my hand. I heard nasty words coming out of my mouth. The rain soaked us, relentlessly. Two stray dogs appeared on the other side of the fence, inside the Park. They started growling, showing us their teeth.

Milly turned from my hand and attacked them ferociously from the protected side of the fence.

We stood for over a minute, each expecting the other to move first. Some kids, rushing for cover on their bikes, shouted at us: "Weirdos, go home!"

"Mr Lascaris," I said patiently, "please move first. We’re making a spectacle of ourselves."

I kept still as he pushed his right shoulder backward, causing me considerable pain. As he dragged his left foot out with his usual slow majesty, I bounced forward, breathing free at last. My chest was aching and my hand was bleeding from Milly’s sharp teeth.

"This is a charming incident," he said, straightening his clothes. The rain still saturated us. The thick lenses of his antediluvian glasses were streaming with water.

Suddenly he stopped. Solemnly and calmly he turned to me, raising his right hand in its commanding position.

"From this moment we shall call this opening the Lascaris Crossing. It indicates the impossible symbiosis between dissimilar people."

I could sense the immense euphoria of his whole body. Mine had already started shivering.’

(From The crossing)

‘It was raining in Sydney. Then there was scorching sun. After a while, for several hours, fog covered the city. The skyline disappeared. People were like wet plastic animals moving aimlessly. The sun came out again. I closed my eyes and remembered the snowy redemptive monotony of Russia, Finland, Holland.

I was translating A Cheery Soul. Translator’s dilemma: how do we render into Greek dog is "God" turned around– and the rest? How do we turn into another language Australian colloquialisms? Thankless, time-consuming, mind-devouring task: pizza, cholesterol, self-hypnosis were the only ways out.

The phone rang. His voice:

"You have disappeared, Mr Vrasidas."

"I’m sorry," I replied, somehow embarrassed, "but I have so much to do. Plus some family problems back there. And last but not least that play by Patrick. Why did he write plays? There is no tragic sentiment today. Language cannot give birth to confrontation with our destiny. Why did he write plays?"

Long silence. Was he bored by this and similar questions? Or maybe he was trying to find the right answer? Then as usual he started talking about something completely different.

"You know," he said rolling the Greek word xerrrreteeee on his lips, "you know, prose is always sad and sober, whereas poetry implies an element of jocularity. Prose always poses problems of style, of rhythm, of punctuation. Poetry is like the accordion: you can suspend it and close it as many times as you like, especially today. For Patrick, theatre was a hybrid state between soberness and frivolity. I thought that sometimes he overdid it. But when he is successful, you must admit that his words breathe like tangible beings. You know, deep down Patrick was a religious personality, so he was prone to turning romantic, especially when he was pretending to hate romanticism. But he always started with complexities and ended with terrifying simple truths. Theatre gave him the faces of actors so that everything would seem normal– even when the normal was an awesome threat."

"I can’t follow you," I said. "You are so elliptical today, so fragmented. Is everything fine?"

"Perceptive– that’s really unusual for a Greek! I am not a critic, as you know, buuuut–" he laughed ironically, “I remembered today when I last saw my mother as a child. The weather brought back that hazy feeling of old fragrances, clothes, rooms, shoes. You understand: the colour and the texture of lost objects. I suppose that in some instances we must ask ourselves the crucially stupid question Where am I?– and when you ask something like that, you must be in a state of confusion."

He took a deep breath. He was encouraging himself.

"It has nothing to do with memories, or nostalgia. It simply means How did I get here? Sydney is the metropolis of solitude. In Alexandria you didn’t have the time to feel alone; you couldn’t be alone; you were swimming in an endless sea of encounters. But Sydney is different. I’ve lived here for most of my life now and I think that I know the truth. It’s the city of loners– strictly speaking, of orphans. It is a city inhabited by children, innocent, unsuspicious, sinless, living in utter solitude. Can I tell you something? Well, these children commit sins because they want to cease being alone; they want to be noticed, recognised, seen! And the worst of all is that they cannot say the simple sentence: Look at me, I exist! And I will tell you something more, because you have to grow up at a certain point in your life–"

Did I open my mouth?’

(From Lost objects)

|